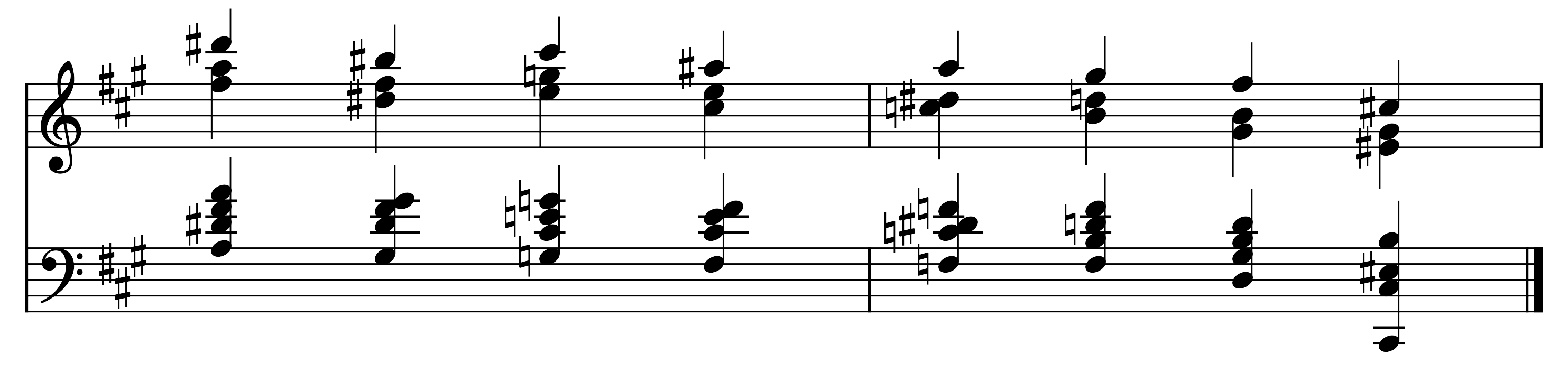

Figure 1: The opening measures of Chopin's Prelude #1 and of the Prelude #1 from J.S. Bach's WTC I2

by

Brent Hugh

brent@brenthugh.com

May 2000, revised May 2024

Analysis and research in support of final Doctoral of Musical Arts Recital

performed 14 March 2000

University of Missouri-Kansas City

Conservatory of Music

Kansas City, Missouri

Note: This work is also available as a PDF file: Chopin Preludes, Ravel Valses Nobles et Sentimentales, and Bartók Piano Sonata: Background, History, and Analysis by Brent Hugh

PREFACE

On March 14th, 2000 I performed my final doctoral recital at the University of Missouri-Kansas City's Grant Hall. On the program were the Preludes, Opus 28, by Frédéric Chopin, the Valses nobles et sentimentales by Maurice Ravel, and the Piano Sonata by Béla Bartók. This recital paper explores the significance of these three works, putting them in historical context and investigating the important musical forms and techniques used in them.

All three works are long works made up of a series of smaller parts, the smaller parts being preludes, waltzes, and movements, respectively. The essential musical problems in any multi-part work are the same: How do the parts of the work relate to each other? How do the parts relate to the whole work? How can one unified work be made from a series of separate and distinct parts?

In each of the three works discussed, the small constituent parts are related to each other and to the whole using a dazzling array of compositional and musical devices, some unique to that particular work and some common to all three works: Musical ideas, motives, harmonic progressions, and compositional processes are shared among the various parts; parts are dovetailed together; boundaries between parts are here blurred and there accentuated; parts mirror, develop, and recapitulate musical motives and ideas found in other parts; parts contrast and complement each other; a series of small parts becomes part of a single larger compositional design; small sub-parts use similar developmental and compositional processes as medium and large parts.

Each work presents a mystery or two. Why does one of Chopin's preludes delay the entrance of its tonic chord until the final two measures? Why does another prelude end on a chord other than its tonic? Why did Ravel, a serious composer, choose to write a work based on that super-popular and rather frivolous genre, the waltz? Why are quotations from one of the waltzes omitted from the "Épilogue" when quotations from all other waltzes are included? Why does the Bartók Sonata's first movement present so many seemingly unrelated themes? Where does the unique harmony in the Sonata's last movement come from?

In each case, the solution to the mystery casts particular light on

the relation of the parts to the whole of a composition, or the whole to

the parts. Solving the mysteries presented by each work, then, will reveal

a part of the work's essence, unveiling its compositional techniques and

illuminating its place in musical history.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE *

Frédéric Chopin: Preludes, Op. 28 *

Preludes No. 1-14 *

Interlude 1: The Story *

Preludes No. 15-21 *

Interlude 2: Connections *

Prelude No. 22-24 *

Postlude: The Preludes as a Set *

Waltz II: Assez lent-avec une expression intense *

Waltz III: Modéré *

Waltz IV: Assez animé *

Waltz V: Presque lent--dans un sentiment intime *

Waltz VI: Vif *

Waltz VII: Moins vif *

Waltz VIII: Épilogue-Lent *

Movement II-Sostenuto e pesante *

Movement III-Allegro molto *

FOOTNOTES *

WORKS CITED *

Frédéric Chopin: Preludes, Op. 28

Prelude to the Preludes: History

The prelude is one of the most ancient genres of idiomatic keyboard music. Designed to introduce the general mood, tempo, and key of the main work that followed, the early prelude was not intended to stand alone but was the mere introduction that its very name suggests. Keyboardists undoubtedly improvised the earliest preludes, but soon favorite preludes were written down so that they could be used again and taught to students. For instance, the Ileborgh Tablature (1448), one of the earliest known examples of notated keyboard music, has five short preludes in different keys.

Much keyboard music in the late Medieval and early Renaissance periods consists of simple arrangements (intabulations) of choral or instrumental music. In contrast, the prelude stands out as a genre used by composers to explore the particular capabilities, sonorities, and textures especially well suited to keyboard instruments. For instance, Praeambulum bonum super C from the Ileborgh Tablature explores scale figurations, accompaniment in 3rds and 6ths, and full block chords. The Praeambulum super C from the Buxheim Organ Book (c. 1475) has virtuosic scalar passages of a type designed to fit the organist's hand easily.

Although the earliest preludes were meant to be introductory, the continual publishing of Preludes and the experimentation of composers and improvisors soon led musicians to think of the "preluding" style and to think of Preludes as works that could be either introductory in nature or complete in themselves.

From these earliest collections of preludes, musicians had an interest in collecting preludes in different keys. Partly the reason for this is practical--if preludes are introductory, musicians need a prelude at hand for any key they may wish to introduce. Early tuning systems allowed keyboard instruments to be used in only a few keys, so preludes were written in these keys only. As tuning systems developed that allowed keyboardists to play in keys with more flats and sharps, collections of preludes were written that covered all of the useable keys.

In the late Baroque period, a practice developed of linking a prelude and a fugue, both in the same key. When this practice first developed, the order prelude-fugue was not fixed and was often reversed--reinforcing the idea that composers thought of the prelude primarily as a certain sort of keyboard style and only secondarily as an introductory piece.1

In 1702, Caspar Ferdinand Fischer combined the ideas of preludes in many keys and preludes linked with fugues when he wrote Ariadne music Neo-organoedum, a collection of preludes and fugues in 19 different keys.

J. S. Bach expanded on the tradition of compiling sets of preludes and fugues in different keys when he published his Well Tempered Clavier. Each of the two books of the Well Tempered Clavier has a complete set of preludes and a fugues in the 24 possible major and minor keys. The preludes and fugues are arranged in chromatic order, with the prelude and fugue in the major key followed by the prelude and fugue in the parallel minor key.

Chopin inherited the genre of the prelude with its rich history, and although he expanded its boundaries, the main outlines of the historical genre are still evident: Chopin's Preludes, like their historical antecedents, are short, improvisatory works that explore textures and capabilities unique to the medium of the keyboard, they typically explore a single mood, texture, and musical idea, and they are grouped in a set of 24 covering all major and minor keys.

Of all the historical sets of preludes, Bach's Well Tempered Clavier was Chopin's primary model--Chopin kept a copy of the Well Tempered Clavier on his music stand as he worked on the Preludes. Like Bach, Chopin composed 24 preludes, one in each major and minor key. Unlike Bach, Chopin's Preludes follow the order of the circle of fifths: C, a, G, e, D, b, A, f#, E, c#, B, g#, F#, eb, Db, bb, Ab, f, Eb, c, Bb, g, F, and d.

The Prelude No. 1 in C major owes a clear debt to J. S. Bach's prelude

in the same key (WTC I): both preludes consist of arpeggiated figures outlining

chord progressions. Even the chord progressions of the opening measures

of the two preludes are remarkable similar (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The opening measures of Chopin's Prelude #1 and of the Prelude #1 from J.S. Bach's WTC I2

The first measure of Chopin's C major Prelude seems straightforward,

but actually it introduces an ambiguity of a sort typical of the Preludes.

The harmony of the measure is, at first glance, C major and the final melodic

A is a neighbor note (see Figure 1). But the harmony could be an a![]() chord (m. 19, similar to m. 1, is a

chord (m. 19, similar to m. 1, is a![]() in context) or some bi-tonal combination of C major and A minor. Which

is the "real" harmony of this measure? In context, it can only be C major,

but it must be admitted--for a moment, anyway--that there are alternate

possibilities. These alternate possibilities are not accidental: all of

them will be explored later in the Preludes.

in context) or some bi-tonal combination of C major and A minor. Which

is the "real" harmony of this measure? In context, it can only be C major,

but it must be admitted--for a moment, anyway--that there are alternate

possibilities. These alternate possibilities are not accidental: all of

them will be explored later in the Preludes.

The second piece in Bach's Well Tempered Clavier Book I is the fugue in C major. In a way typical of Bach's musical symbolism, the fugue prefigures the entire set of 24: during the course of the fugue, the fugue subject enters exactly 24 times. Could Chopin, with a copy of the Well Tempered Clavier constantly at his side, have known or noticed this? It is an intriguing question, because, in a similar way, the second piece in Chopin's set, the Prelude in A minor, prefigures several aspects of the entire set of preludes.

The A minor Prelude, with its dissonant, dirge-like accompaniment pattern and seemingly wandering harmonic scheme, is possibly the strangest and most difficult prelude from the harmonic point of view. But many of these difficulties vanish when the prelude is seen is as a reflection in miniature of the idea of the Preludes as a whole.

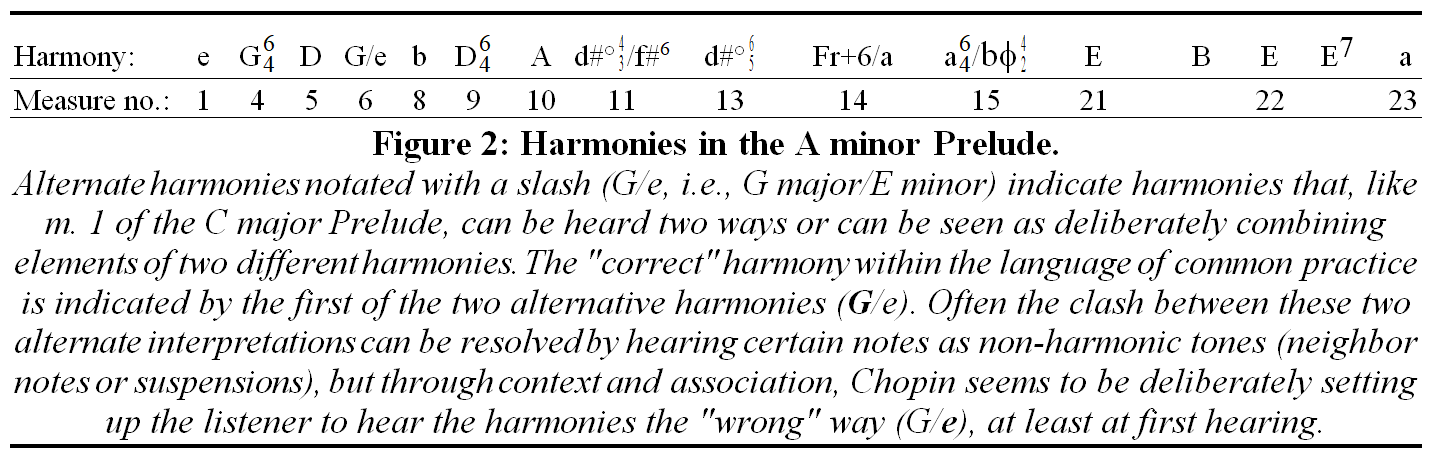

The harmonic scheme of the prelude at first glance seems wandering, improvisatory, and perhaps even aimless (see Figure 2).

Here is a prelude, clearly (because of the tonal scheme of the Preludes) in the key of A minor, which does not introduce the tonic or its dominant until the second measure from the end (in retrospect, m. 15 and even m. 11-14 can be heard as dominant preparation, but this preparatory function is clear only in retrospect, after the impact of the final cadence in mm. 22-23 has been absorbed).

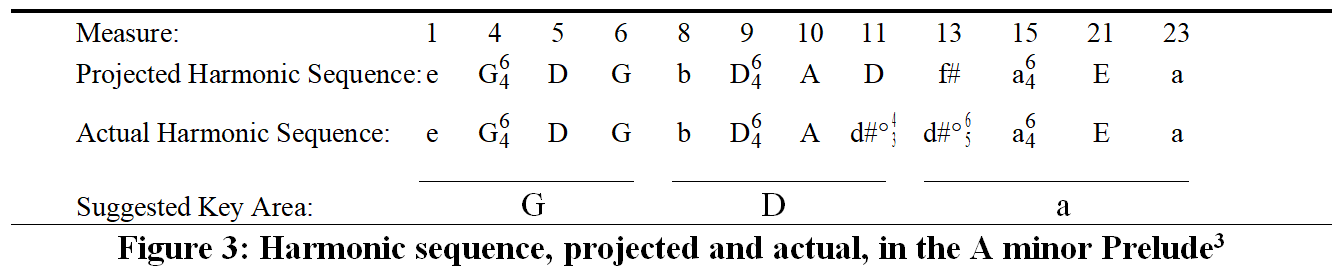

The phrase structure and melodic direction, too, seem irregular and aimless at first glance. Here is a prelude that harks back to the aimless wanderings of musician's fingers that first defined the genre. Yet at the heart of this seeming chaos is, in fact, a simple and straightforward harmonic sequence (see Figure 3).

The "Projected Harmonic Sequence" follows to its logical conclusion the pattern that is set up in the first 10 measures of the prelude. The "Actual Harmonic Sequence" shows the harmonies as actually written--these differ from the projected harmonies only in mm. 11-14, and even there, the actual and projected sequences share common chord tones.

This "hidden" harmonic sequence that forms the backbone of the A minor Prelude foreshadows in some remarkable ways the harmonic outline of the Preludes as a whole:

The Prelude in G major, with its rapid, leggiermente figurations in the left hand accompanying a slower right-hand melody, has an expanded parallel period structure typical of many of the preludes. After the initial material is presented, there is a brief excursion to the dominant. The initial material is repeated, again in tonic, and another brief excursion leads to the final cadence (see Figure 4).

| Measure: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Section: |

|

|

||||

| Melodic Material: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Key areas: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

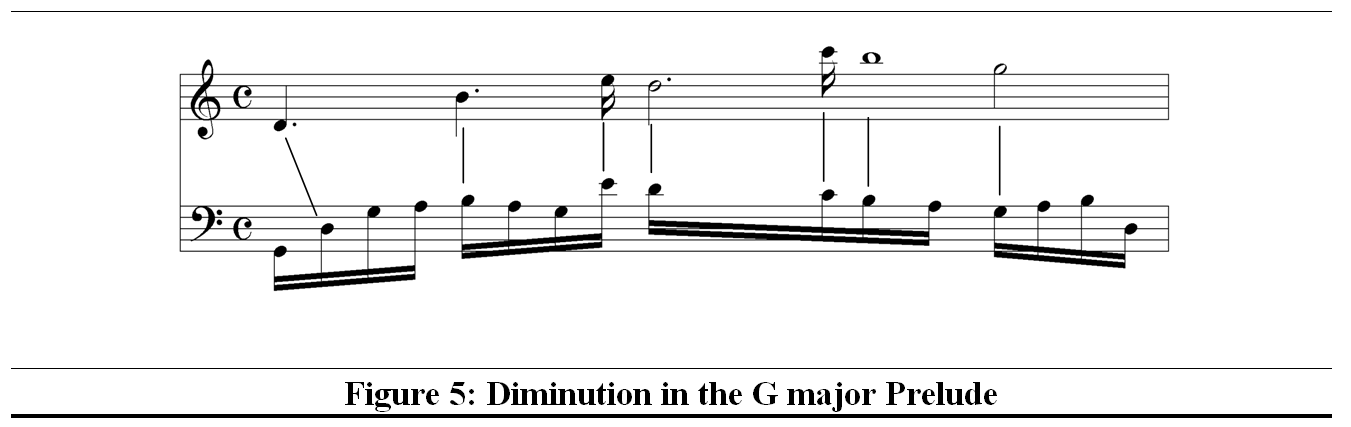

This prelude, like the A minor Prelude, contains a remarkable diminution: the accompaniment figure outlines the main melodic figure at approximately quadruple speed (see Figure 5).

With its extended series of interlocking suspensions and resolutions in the accompaniment, this Prelude in E minor is a great contrast to the preceding G major Prelude. Again the parallel period form is followed. Here, as in no fewer than 11 of the 24 preludes, the final codetta is a brief cadential progression with chordal texture:

These cadential progressions in the Preludes are always set off from the remainder of the prelude by a change in texture and are often articulated by changes in rhythm, by phrasing, or by a rest preceding it. These final progressions point directly back to the purpose of the ancient keyboard prelude, whose primary function was to clearly establish the key; many of the historical preludes are little more than decorated cadential progressions. Chopin's preludes, however advanced they are in other respects, retain this basic functional purpose.

The Preludes have been called "Etudes in Texture" and none of the preludes establishes both ends of this description more quickly than the Prelude in D major. The first four measures establish an elaborate rhythmic texture with no less than three distinct, conflicting layers in a complicated, hemiola-like arrangement:

| Measure |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Meter (3/8) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

| LH figure/RH outer figure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| RH inner melody |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 6: Layered rhythmic groupings in the D major Prelude, mm. 1-5

The LH figure has a hemiola-like relationship to the meter; the RH inner melody is hemiola-like, too, but offset from both the meter and from the LH figure. The result is a complex "rhythmic dissonance" that is not fully resolved until the final two chords of the prelude.

In mm. 5-11, the meter becomes a more regular 3/8. However, both the left-hand and right-hand figurations occasionally hint at an upper and a lower voice within the single melodic line. These figurations create a certain rhythmic instability, because these hints of upper and lower voices most often fall not on 1, but on the and of 1. This syncopating effect is taken a step further in the culmination of this passage (mm. 12-16), when both right and left hands break into clear upper and lower contrapuntal lines:

The rhythmic dissonance created by this extended syncopation is resolved by the downbeat of m. 17, but immediately the hemiola figure of mm.1-4 returns with its conflicting layers of rhythmic activity. Only with the cadential formula (mm. 37-39) and associated break in the texture is the rhythmic dissonance ultimately resolved.

The Prelude in B minor is reminiscent of Chopin's "Cello" Etude, Op. 25, No. 7: it features an emotive melody in the left hand accompanied by a simple ostinato-like figure in the right hand. As in the "Cello" Etude, the outer voices sometimes join to make an expressive duet (mm. 6-8). Like many of the parallel period preludes, the "excursion" in the B minor Prelude's second phrase is longer and goes further afield. The codetta is based on the initial motive.

Perhaps simplest of the set and among the shortest, the A major Prelude consists of a single rhythmic motive repeated eight times:

The form is perfectly symmetrical and balanced, breaking into halves exactly three times (see Figure 7).

| Phrase

Structure

|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Harmony |

|

|

|

|

|

Aà

F#7 b7à E7 A A

|

|||||||||

| Measure no. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

The Prelude in F# minor is again of the type in which a fast-moving keyboard figuration overlays a slower-moving chord progression. The prelude is marked "molto agitato" and the agitation is portrayed by a fast-moving, closely spaced line in the right hand with chromatic dissonances and resolutions, an incessant 3 against 4 rhythm, highly chromatic harmonic progressions, and a searching, chromatic inner melody. The rhythm is relentless--the initial rhythmic pattern is repeated 127 times, and only in the final cadential pattern (mm. 33-34) is there release from it.

Grouping the right hand according to the figuration leads to a sequence of chords. The right hand, taken alone out of context, seems to make little sense as a harmonic progression. Bars 7-8 are a typical example of this:

Grouping the four adjacent notes of each right-hand figure leads to this nonsensical chord progression:

Analyzing the chord progression and removing non-harmonic tones (most of which are simple passing tones, appoggiaturas, and suspensions) leaves this chromatically descending underlying chord progression:

As he did in the A minor Prelude, Chopin is using the figuration to group the notes in such a way as to accentuate their coloristic, non-tonal role. Yet behind this coloristic, non-functional surface is always a completely tonal backdrop with clear, functional harmony and careful preparation and resolution of dissonances. It is this way of speaking two languages at once that allows Chopin's music to be traditional harmonically and yet at the same time strikingly colorful and original.

The E major Prelude consists of three phrases, each starting with a similar I-V motive in E major:

| Phrase Length: | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Measure no.: | 1 | 5 | 9 |

As with the parallel period preludes (of which this is but a slight variation, the third phrase playing the part the codetta did in previous preludes), the first excursion stays closer to the tonal center, while the second excursion (2nd phrase) is far more adventurous, taking the listener from E major to C major, A major, Ab major, and back again, all in the space of four measures (m. 5-8).

This prelude has a three-layered texture with the middle layer filling in harmonies and providing an incessant pulse in triplet eighth notes. The main dramatic conflict stems from the interplay between the outer two lines, which begin each phrase exchanging periods of rhythmic activity but become more equally active during points of higher intensity (in this way it is quite similar to the B minor Prelude). Much of the rhythmic intensity comes from the juxtaposition of triplet eighth-note rhythms (middle voice), dotted-eighth-sixteenth-note rhythms (most often in the upper voice) and double-dotted-eighth-32nd-note rhythms (always in the bass until the final three measures when they infiltrate the soprano, as well) (see Figure 8).

The combination of these measured rhythmic pulses at the marked tempo

of largo with a unyielding harmonic rhythm creates the sense of

fateful inevitability that characterizes this prelude.

Figure 8: Triplet/dotted/double-dotted rhythms in the E major Prelude (mm. 6-7)

Two distinct textures regularly alternate in the C# minor Prelude (see

Figure 9). The first texture (Texture A) is made of fast, descending leggiero

figurations in the treble with occasional widely spaced rolled chords in

the bass. The second texture (Texture B) is a homophonic chordal texture,

over a generally dominant pedal point. In its regular phrase structure

and brevity, this prelude is reminiscent of the A major Prelude.

| Length: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Key center: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Texture: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Measure no.: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The B major Prelude is in many ways reminiscent of the D major Prelude: the jagged Vivace outline of the upper line suggests within a single line a contrapuntal conversation between two lines, and the lower line outlines its chords with a series of irregular arpeggiated figures. Like the D major Prelude, this prelude falls into two roughly parallel halves (defined by the return of the a material), makes a sort of codetta from the return of the introductory material, and concludes with two cadential chords that contrast in texture with the remainder of the prelude (see Figure 10).

Unlike the D major Prelude, both right-hand and left-hand figurations

in the B major Prelude tend to reinforce the meter and the prelude is rhythmically

uncomplicated.

| Length: | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Material: | Intro | A | A | b | a | a | Intro | Cadence |

| Measure no.: | 1 | 3 | 7 | 11 | 15 | 19 | 21 | 26 |

The G# minor Prelude, with its breathtaking perpetual motion of chromatic

eighth notes, is much longer than the B major Prelude, yet in formal outline

remarkably similar (see Figure 11).

| Length: | 8 | 12 | 20 | 8 | 16 | 17 | ||

| Material: | A | A | B | A | A | Coda | ||

| Measure no.: | 1 | 9 | 21 | 41 | 49 | 65 |

Much of the energy (and technical difficulty for the performer) of the

prelude comes from pairs of repeated notes that characterize the melodic

line. Throughout the prelude, with very few exceptions, the second eighth

note in each beat is repeated as the first eighth note of the following

beat. This device creates not only a driving, motoric rhythmic force, but

also a strong sense of rhythmic and harmonic intensity. The half-beat offset

between the movement in the melodic line and the movement in the lower

voices creates rhythmically a syncopated effect and harmonically a kaleidoscopically

varied series of anticipations, ritardations, suspensions, and passing

tones (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: Syncopated effect created by repeated notes in the G# minor Prelude

In eleven of the first twelve preludes, one single texture and tempo ruled each prelude (and in the remaining prelude, No. 10 in C# minor, two textures alternated in a simple fashion). The brevity of these preludes, the predominance of single textures featuring idiomatic keyboard figurations, their improvisatory style, and their simple formal structure show the debt these preludes owe to the centuries-old tradition of keyboard preludes.

Although the F# major Prelude still clearly falls within the general tradition of the prelude, in several ways it breaks the mold set by the first twelve preludes of the set. It is by far the longest prelude so far, the first to fall into a clearly defined ABA form, and the first to have long sections with clearly distinguished tempo, mood, and texture.

In mood, tempo, form, and texture, the F# major Prelude resembles a compressed nocturne. In the A section, the slower moving right-hand and bass lines surround a faster moving inner part in the left hand that outlines the harmony in an arpeggiated figuration fairly typical of a nocturne. When phrases are repeated in the soprano, some of the ornamental melodic variation typical of Chopin's nocturnes is found.

The B section is slower ("Piu lento") and in it the inner voices assume a homophonic chordal texture in which the three voices assert themselves in turn with stepwise melodic fragments. The soprano is reduced to a single melodic line (in the A section it is generally a homophonic chorus of three voices), though it still moves at a much slower speed than do the lower voices.

On its return, the A section is abbreviated and intensified by increasing the number of voices in the homophonic right-hand part from three to four. The brief coda is based on material from the B section.

The Eb minor Prelude is a return to the brief, two-part form characteristic of the first twelve preludes. A single texture holds sway throughout the prelude, which in many performances is shorter than twenty seconds in duration.

This brevity and unusual texture (the two hands articulate a single melodic line in octaves) inevitably suggest parallels with the finale of Chopin's Bb minor Sonata. The finale has a similar texture and, although significantly longer than the Eb minor Prelude, is as proportionally brief a sonata movement as the Eb minor is a prelude.

As in the D major Prelude, much of the rhythmic and harmonic tension of this work stems from the interplay among several different layers of rhythmic and melodic activity (see Figure 13).

Only in the final five measures does this complicated rhythmic dissonance begin to resolve, as first the lower line (mm. 15-16) and then the upper line (mm. 17-18) asserts its dominant rhythm and the others fade into the background.

That Chopin is able to support such a complex, layered rhythmic structure,

along with an equally complex and dense harmonic and melodic configuration,

all within a single melodic line makes this tour-de-force of compositional

virtuosity a highlight of the set.

Chopin's idea to compose a set of preludes may have been conceived as early as 1831, but the earliest known manuscript of any of the preludes dates from 1836 (the A major Prelude, written out for Delfina Potocka4). But there is little doubt that much of the work on the Preludes--finalizing any preludes already begun and composing the remainder--took place in late 1838 and early 1839 in Majorca.

Chopin and George Sand (the pen name of Aurore, Baronne Dudevant, a well-known novelist and Chopin's friend, companion, and lover) had planned this extended visit to Majorca to improve Chopin's failing health. Although the climate and rustic atmosphere were reputed to be helpful for convalescence, in fact the primitive conditions and cold worsened Chopin's already precarious position:

Although it was not really that cold, never have I suffered more from cold: for us who are used to heat in the winter, this house without a fireplace was like a mantle of ice on our shoulders . . . [O]ur invalid began to suffer and to cough.5

The party was forced to leave its first accommodations and spend the remaining months of the stay in an abandoned monastery high in the hills. The conditions were difficult all around--the arrival of Chopin's Pleyel piano was delayed interminably by inept transportation and customs officials, so for months he made do with a small, local piano, barely in playable condition. But in January, 1839 Chopin sent the finished manuscript of the Preludes to Julian Fontana in Paris, and by the time Chopin returned to Paris in October, 1839, both the French and German editions of the Preludes had appeared.

George Sand, in her books Un Hiver en Majorque (A Winter in Majorca, 1841) and Historie de Ma Vie (Story of My Life, 1853), gave many imaginative details about the stay in Majorca and the conditions and states of mind of Chopin and his group as he composed the Preludes. Historians have tended to discount the literal details of Sand's accounts; there is little doubt that Sand was more interested in portraying the psychological and artistic heart of the situation than its literal truth. Her stories tell us perhaps more about George Sand and her creative viewpoint than about Chopin and his.

Undoubtedly the most famous example of this writing is traditionally linked with the Prelude in Db major. Sand wrote:

There is one that came to him through an evening of dismal rain--it casts the soul into a terrible dejection. Maurice and I had left him in good health one morning to go shopping in Palma for things we needed at our "encampment." The rain came in overflowing torrents. We made three leagues in six hours, only to return in the middle of a flood. We got back in absolute dark, shoeless, having been abandoned by our driver to cross unheard of perils. We hurried, knowing how our sick one would worry. Indeed he had, but now was as though congealed in a kind of quiet desperation, and, weeping, he was playing his wonderful Prelude. Seeing us come in, he got up with a cry, then said with a bewildered air and a strange tone, "Ah, I was sure that you were dead."

When he recovered his spirits and saw the state we were in, he was ill, picturing the dangers we had been through, but he confessed to me that while waiting for us he had seen it all in a dream, and no longer distinguishing the dream from reality, he became calm and drowsy. While playing the piano, persuaded that he was dead himself. He saw himself drowned in a lake. Heavy drops of icy water fell in a regular rhythm on his breast, and when I made him listen to the sound of the drops of water indeed falling in rhythm on the roof, he denied having heard it. He was even angry that I should interpret this in terms of imitative sounds. He protested with all his might--and he was right to--against the childishness of such aural imitations. His genius was filled with the mysterious sounds of nature, but transformed into sublime equivalents in musical thought, and not through slavish imitation of the actual external sounds. His composition of that night was surely filled with raindrops, resounding clearly on the tiles of the Charterhouse, but it had been transformed in his imagination and in his song into tears falling upon his heart from the sky.6

Sand does not specify the key or number of the prelude written on this occasion, and, although the Db major Prelude is usually given the informal title "Raindrop", in fact the story could apply to any of the melancholy preludes with a repetitive figure (A minor, E minor, and B minor come to mind, as well as Db major).

The Db major Prelude is in many ways like the F# major: it is long (the longest of the set in performance time) and has a clear ABA form. As in the F# major Prelude, the return of the A section is shortened--the internal aba structure of the initial A section is reduced to a single a-- and the short codetta is reminiscent of the B section. The B section is in the parallel minor (spelled enharmonically as C# minor), a shift that is foreshadowed in the B section of the F# major Prelude (mm. 22-23): there, too, the harmony moves rather strikingly from C# major to C# minor.

Most of the preludes are an expanded or contracted version of the same

formal plan. In its smallest size, this form is nothing but a parallel

period (C major, E minor, D major, Eb minor, etc.). In its largest forms

(F# major, Db Major) it becomes a ternary form with coda. The coda is invariably

based on the B theme, however, and this feature relates the larger version

of the form with the simple parallel period form (see Figure 14):

The harmonically unstable end of the a section in the Small Version of the form naturally becomes the B section in the Large Version. In the Small Version, this ending is repeated in a different harmonic context in a', and in the Large Version this becomes a coda based on the B material.

Like the G# minor Prelude, the Bb minor Prelude represents a middle-sized

version of this same basic form (see Figure 15).

Figure 15: Phrase analysis of the Bb minor Prelude

As in the G# minor Prelude, the b material not a single key area, but rather a modulatory sequence leading through several different keys and finally to the dominant. In both preludes, the return of the a material is a literal repeat, except that the bass line is "supercharged"--in the G# minor Prelude by a stepwise descending bass line (it had previously been a static pedal point) and in the Bb minor Prelude by a doubling of the bass line, previously single note, in octaves.

The Prelude in Ab major is again the "middle-sized" version of the prelude

form (see Figure 16).

| Length: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Section: |

|

|

|

||||||||

| Phrase: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Measure no.: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The "in between" phrases (b and c) are not large enough, nor stable enough harmonically, to really be considered separate, independent sections. As they are in the G# minor Prelude and the Bb major Prelude, these phrases share the texture and general melodic and rhythmic feeling of the a phrases. Yet the b and c phrases are distinct phrases with clear cadence points and a distinct melodic and harmonic contour (the harmonic contour is again a sequence of modulations). In short, this form is perfectly poised--halfway between the Small Version (where the b-c phrases would be but the ending of a phrase, slightly different in each half of the parallel period) and the Large Version (where the b-c phrases would be different in texture and significant enough to be considered a separate section of the piece).

The coda of the Ab major Prelude is worth special mention. The melody is based on the a theme, but an extraordinary Ab pedal point is held throughout the entire 26 measures of the coda. I. J. Paderewski, who studied with Camille Dubois, a student of Chopin, said:

I remember once when I was playing the 17th Prelude of Chopin, Madame Dubois said that Chopin himself used to play that bass note in the final section [bars 65 ff.] (in spite of playing everything else diminuendo) with great strength. He always struck that note in the same way and with the same strength, because of the meaning he attached to it. He accentuated that bass note--he proclaimed it, because the idea of that Prelude is based on the sound of an old clock in the castle which strikes the eleventh hour. Madame Dubois told me that I should not make that note diminuendo as I intended, in accordance with the right hand which plays diminuendo continually, but said that Chopin always insisted the bass note should be struck with the same strength--no diminuendo, because the clock knows no diminuendo. That bass note was the clock speaking.7

Prelude No. 18 in F Minor

The Prelude in F minor is a return to the type of prelude closely tied

to improvisation. The work unfolds in a rhapsodic manner, with each phrase

picking up and expanding an idea from

the previous phrase. The initial motive, played in m. 1 and repeated

in m. 2, is expanded in mm. 3-4 (see Figure 17). The initial phrase (mm.

1-4) is repeated at a different pitch level and expanded in mm. 5-8. In

mm. 9-13, the end of the cadenza-like figure in m. 8 is expanded in size

of interval, number of notes, and length--finally (mm. 12-13) becoming

a cadenza-like figure faster and more precipitous than the original. In

mm. 14-15, the final notes of this outburst in m. 13 are repeated, on each

repetition expanded by ever-increasing intervals. The rhythmic values are

foreshortened, first taking half the time of the original (m. 15) and then,

compressed further, one-fourth the time (m. 16). This increasing rhythmic

energy, aided by ever-widening melodic leaps, leads to a final cadenza-like

lightning stroke and, after a long pause, a thunderous final cadence.

Figure 17: F major Prelude, repetition and expansion of initial motive (mm. 1-4)

In texture and general outline, several of the preludes parallel other of Chopin's works. Often these parallel works are in the same or similar keys, and always the prelude is the more compact of the two works. For instance, the C major Prelude is based on arpeggiated figures, as is the C major Etude, Op. 10, No. 1 (both works owe a debt to Bach's C major Prelude). The B minor Prelude is similar to the "Cello" Etude, Op. 25, No. 7, and the Eb minor Prelude is strikingly similar to the finale of Chopin's Bb minor Sonata. The F major Prelude bears an undeniable resemblance in texture to the F major Etude, Op. 10, No. 8.

The Prelude in Eb major, too, shows a strong family resemblance to an etude in a similar key: the "Aeolian Harp" Etude in Ab major, Op. 25, No. 1. The prelude and the etude are similar in texture, although, as is typical in these parallels, the prelude has a briefer version of the same basic texture. Even the opening melodic anacrusis is similar: in both cases, the upbeat and first downbeat of the melody are on the 5th degree of the scale.

In form, the Eb major Prelude is typical of the middle-sized prelude

form (see Figure 18).

| . Coda . | |||||||||

| Length | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Material | A1 | A2 | B1 | B2 | A1 | A3 | D1 | D2 | A'' |

| Measure no. | 1 | 9 | 17 | 25 | 33 | 41 | 49 | 57 | 65 |

A major artistic aim evident throughout the entire set of preludes is the principle of contrast. Since the preludes are generally short and of a single uniform texture, there is little contrast within a single prelude. The two longest preludes (F# major and Db major) have a degree of contrast in their middle sections, but even in those cases, the degree of continuity is more remarkable than the degree of contrast. Within a prelude, continuous development of a single idea and texture is the rule.

When moving from one prelude to another, however, there is ample opportunity for variety, and here Chopin seems to be reaching for the maximum possible contrast. It is impossible to find two neighboring preludes that share the same tempo, texture, length, or mood.

For example, the two longest preludes, the F# major and Db major stand on opposite ends of the Eb minor Prelude, the shortest of the set. One of the most lyrical preludes (Db major) is followed by one of the most rhythmically vigorous (Bb minor). An improvisatory prelude with dramatic pauses (F minor) is followed by one with very regular texture and rhythm (Eb major).

A regular alternation of fast (major) and slow (relative minor) preludes is evident in the first six preludes, and the alternation of tempo continues in the remaining 18 preludes, but the order is usually reversed: the major prelude tends to be more lyrical and the minor prelude more vigorous.

The only exception to this slow/fast order in the final 18 preludes

is the pair with three flats: Eb major and C minor. The Eb major Prelude

is far more rhythmically active, with a busy foreground texture overlaying

a slower-moving harmonic rhythm. The C minor Prelude is the opposite, with

a faster-moving harmonic progression but a minimum of rhythmic activity

in its chordal texture. The tempos, too, are at opposite ends of the spectrum

(vivace and largo) and the tessaturas of the two preludes

are contrasting.

| Length: | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Material: | A | B | B |

| Measure no.: | 1 | 5 | 9 |

The form of the C minor Prelude is simple (see Figure 19). Apparently the original form of this piece was simply AB; the repetition of the B section at pp and the final crescendo to f were suggested to Chopin by François-Henri-Joseph Blaze.8

The cantabile Prelude in Bb major is similar to the F# major

and Db major Preludes in its nocturne-like texture (a slow-moving, ornamented

melody in the treble and chromatic accompaniment in the middle register)

and in its middle section with clearly different texture and key center.

Unlike the earlier preludes, the A section never returns literally: the

first two measures of the A3 section appear to be a literal return of the

A material, the only change being in the middle-register chromatic chords,

which are doubled in octaves. But soon the nocturne-like melody is completely

overtaken by these chromatic chords (as they had threatened to do in earlier

in mm. 13-16), and this chromatic figure dominates the rest of the A3 section

and the coda (see Figure 20).

| Length | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 14 |

| Material | A1 | A2 | B1 | B2 | A3 | Coda |

| Key Area | Bb | Bb | Gb | Gb | Bb | Bb |

| Measure no. | 1 | 9 | 17 | 25 | 33 | 46 |

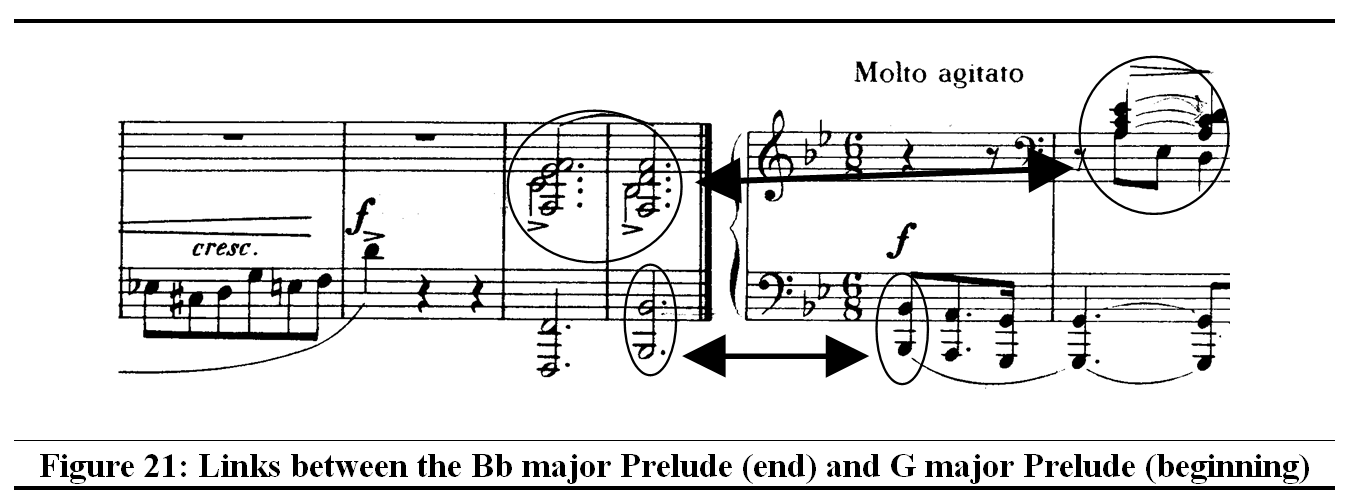

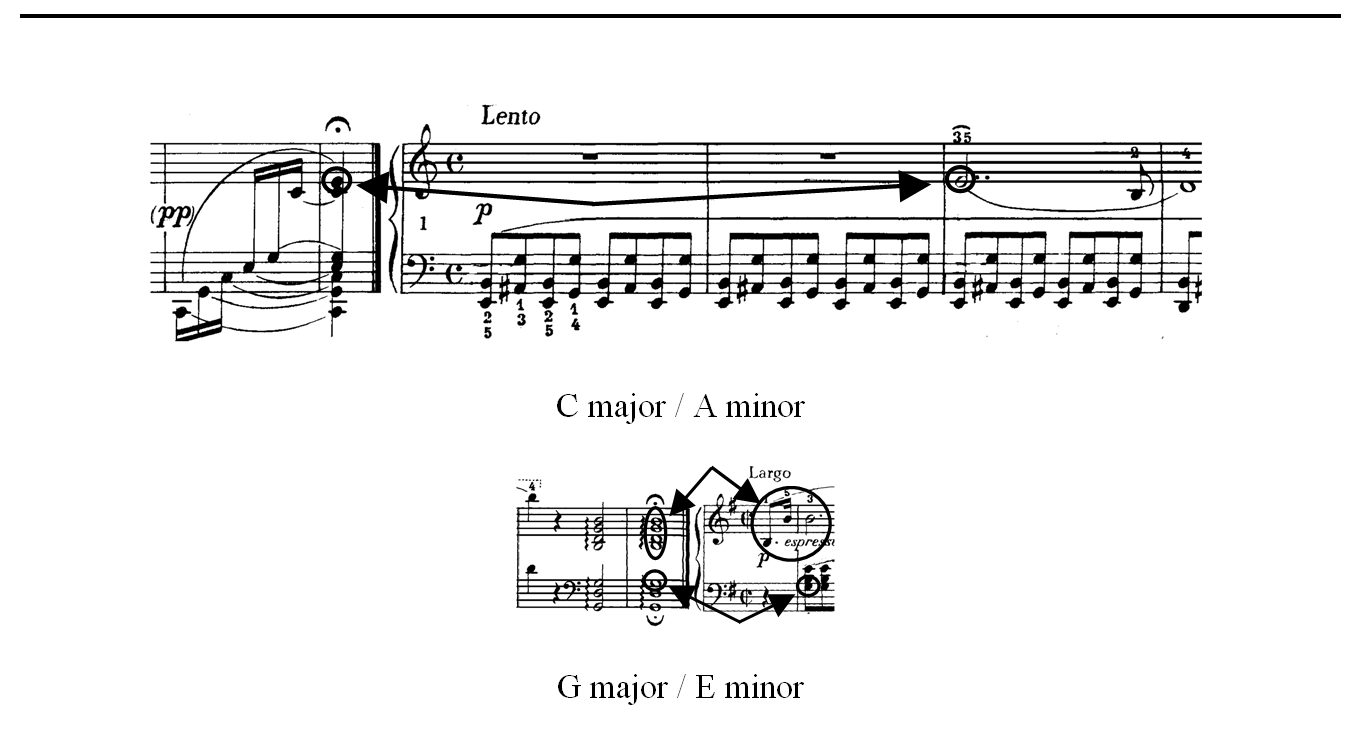

In the Bb major Prelude, the connection between the keys of Bb major (A section) and Gb major (B section) is the tone the two chords have in common, Bb. The connection between the Bb major Prelude and the following Prelude in G minor is likewise the tone common to the B major and G minor chords--again, Bb (see Figure 21). Chopin is at pains in this pair of preludes, and in many of the pairs, to make this connecting tone explicit by ending the major prelude and beginning the minor prelude on this connecting note. Just as in the F minor Prelude one musical idea seemed to grow organically out of the end of the preceding idea (see Figure 17), so in the entire set does one prelude grow organically out of the end of the preceding prelude.

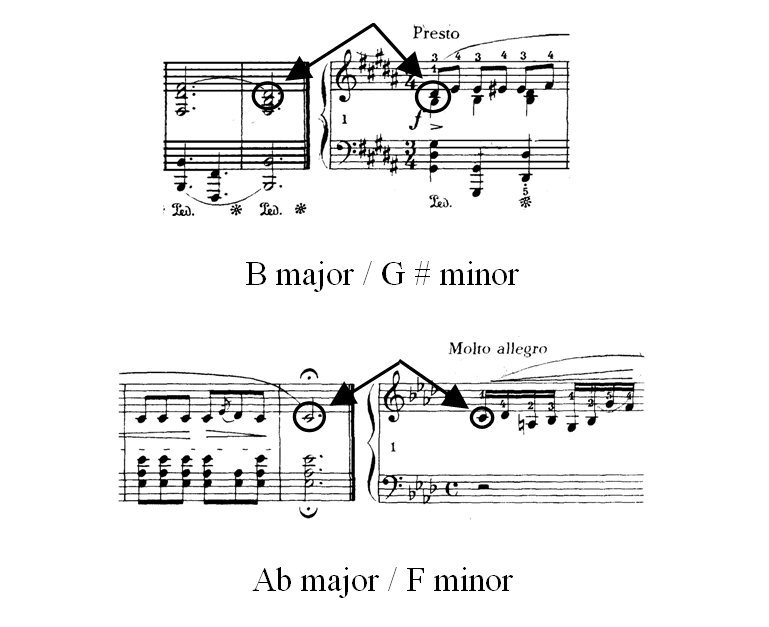

Here, as in so many other ways, the structure and pattern of the whole set of preludes is contained in miniature in the first and second preludes. The second prelude clearly foreshadows the importance of linking via common tones: with a single exception, each of the subphrases in that prelude begins with the final tone of the preceding phrase (see Figure 22). Furthermore, the two preludes are linked melodically through this same device: the final e of the C major Prelude becomes the initial e of the melody in the A minor Prelude (see Figure 24).

But the connection between these two preludes may well go beyond that:

Edward T. Cone has suggested that the strange, wandering key sequence of

the A minor Prelude can be explained by a hypothetical initial phrase (adding

the chord progression a C![]() G

C to the beginning of the harmonic sequence outlined in Figure 3 gives

the prelude a clear opening and close in the tonic). Furthermore, Cone

finds traces of this "missing" initial phrase at the end of the C major

Prelude (see Figure 23).9

G

C to the beginning of the harmonic sequence outlined in Figure 3 gives

the prelude a clear opening and close in the tonic). Furthermore, Cone

finds traces of this "missing" initial phrase at the end of the C major

Prelude (see Figure 23).9

Whether or not this "rather bizarre proposition" (Cone's words) is accepted,

it is clear, even from the first measure of the first prelude, that this

first pair of preludes is designed to introduce the great musical themes

that occupy the entire set of preludes: What is the relation between the

major and its relative minor? and, How can these two related keys be linked

while allowing each to retain its individual identity?

Chopin addresses this second problem by making the pairs of preludes always contrasting and never in any obvious way sharing motives or extended musical ideas. Each prelude has a unique musical character. Yet these contrasting characters are linked in pairs, because one prelude picks up exactly where the previous one left off. This is an improvisor's kind of solution, based on the feel of the keys under the fingers as much as their sound, and often it goes far beyond the relation of the bare notes. For instance, the G Major Prelude ends with the right hand holding octave Bs; the E minor Prelude begins with a dramatic anacrusis featuring this same pair of Bs (this anacrusis was absent in Chopin's initial draft of this work, and added during revision and editing--showing that these connections are quite conscious and intentional). The B major Prelude finishes with a two-measure chordal passage that, for the first time in this prelude, takes on the same voicing as the G# minor Prelude. The G# minor Prelude picks up right where these chords leave off. The Eb major Prelude ends with a pair of chords, ff, again the first appearance of this texture in this work. The C minor Prelude begins with the same soprano note, with the same voicing, dynamic level, and tessitura (see Figure 24).

In all, 10 of the 12 pairs of preludes are connected this way, and 8 of the 10 connections are very obvious: the connection is made between prominent melody notes that share not only the same pitch but also the same octave.

Prelude No. 22 in G Minor

Like the Eb major Prelude, the Bb major Prelude ends with a pair of chords and the texture of the G minor Prelude grows out of these chords. The chords' left-hand octaves become a vigorous melody in octaves in the G minor Prelude and the right-hand chords' closely spaced dissonance-resolution sets the pattern for the answering right-hand chords in the G minor Prelude.

The form is perhaps closest to that of the F minor Prelude: after a double presentation of the initial material, it goes on to new material--related in texture and style, but unrelated melodically. Unlike the F minor Prelude, there is a clear return of the A material in the coda (see Figure 25).

| Length: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Material: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Measure no.: |

|

|

|

|

|

With its delicate right-hand arpeggios and a brief, fragmentary melody

below them, the F major Prelude is one of the most charming of the set.

Part of the charm comes from the gradual rise from the octave above middle

C (m. 1) to the highest octave of the piano (mm.17-18; see the analysis

in Figure 26).

| Length: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Material: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Key Area: |

|

|

|

|

|

| Measure no.: |

|

|

|

|

|

At the end of the A2 section, the left hand arpeggiates a C major chord, and as its highest note it adds the 7th of the chord. This becomes the dominant seventh of F and leads into the F major of the A3 section. At the end of the A3 section the same pattern is followed: the upper note of the F major arpeggios adds a 7th and this leads to Bb. This twice-occurring pattern sets up the most distinctive feature of the prelude: in the final chord, the left hand again adds the seventh of the chord, changing F major into F7. There the prelude ends, the added 7th unexplained and unresolved (see Figure 27).

How can this enigmatic ending be explained? Several solutions have been suggested:

Figure 28: V7-V7/IV progression in the C major Prelude from WTC I, mm. 31-35

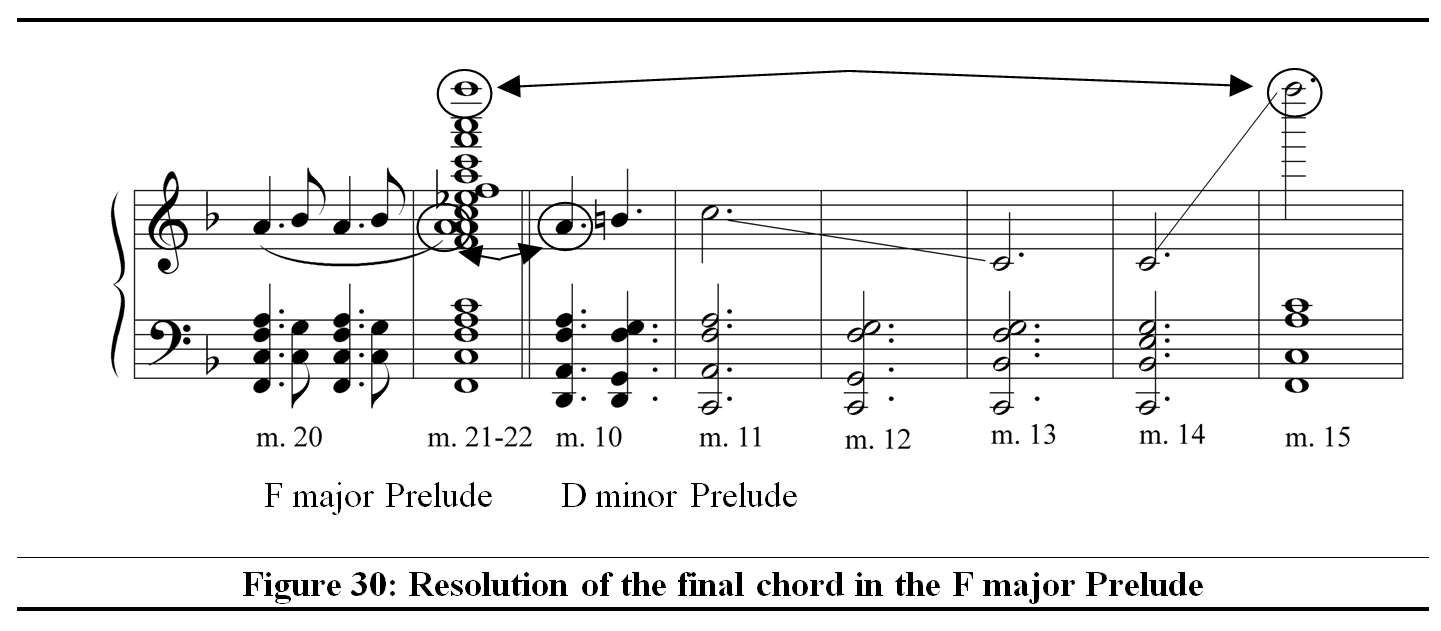

The final prelude in the set immediately reiterates the primary musical concern and interest of the Preludes: the initial phrase moves from D minor to its relative major. A short connecting figure leads to A minor, where the opening material is repeated, leading again to the relative major.

This sequence of phrases, each phrase leading from the minor to the relative major, has appeared before in the Preludes--most significantly, in the A minor Prelude (see Figure 29). In the same way that the A minor Prelude was foreshadowing the harmonic scheme of the entire set (starting the sequence and suggesting that it would run full circle), the D minor Prelude sums up the harmonic progression of the set.

The A minor Prelude begins its movement through the circle of keys with E minor. It moves through several pairs of keys, then trails off. The D minor Prelude picks up the circle, moves around the circle through several pairs of keys, and trails off. Off course there is not space enough in a single prelude to move through all 24 keys, and the D minor Prelude's ultimate tonal goal must be D minor. But where does this sequence of keys break off and begin its return to D minor? Precisely on its arrival at E minor: the cycle of keys in the D minor Prelude ends exactly where the cycle in the A minor Prelude begins. It is as though the sequence of keys suggested in the A minor Prelude has now been completed (see Figure 29). The expectation created in the A minor Prelude has been fulfilled, although in a "hidden" way.

| Key areas in A minor Prelude: | e | G | b | D |

(f#) . . .

|

|

| Key areas in D minor Prelude: | d | F | a | C |

e . . .

|

|

Figure 29: The circle completed: Key areas in the A minor and D minor Preludes

The A minor Prelude goes around the circle of 5ths, beginning with E minor. The D minor Prelude completes the circle that was broken off, ending in E minor.

The connection between the key cycles in the A minor and D minor Preludes suggests a sort of symmetry between the two. The very position of the two preludes (beginning/end of the set) suggests a certain possibility of symmetry. Can this symmetry be taken a step further?

Cone has suggested that the A minor Prelude has a hypothetical first phrase that appears in disguised form in the previous prelude. Let us explore a further "bizarre proposition": suppose that, by symmetry, this "missing phrase" at the beginning of the set is mirrored at the end of the set. What would be the ramifications of this?

The second prelude begins strangely, not on the tonic. The mirror of this would be, that the second to last prelude will end strangely, not on the tonic. The solution to the second prelude's strange beginning turned out to be that its "real" beginning lay within the first prelude. The "mirror" of this solution, then, would be that the "real" ending of the second to last prelude will be found in the last prelude.

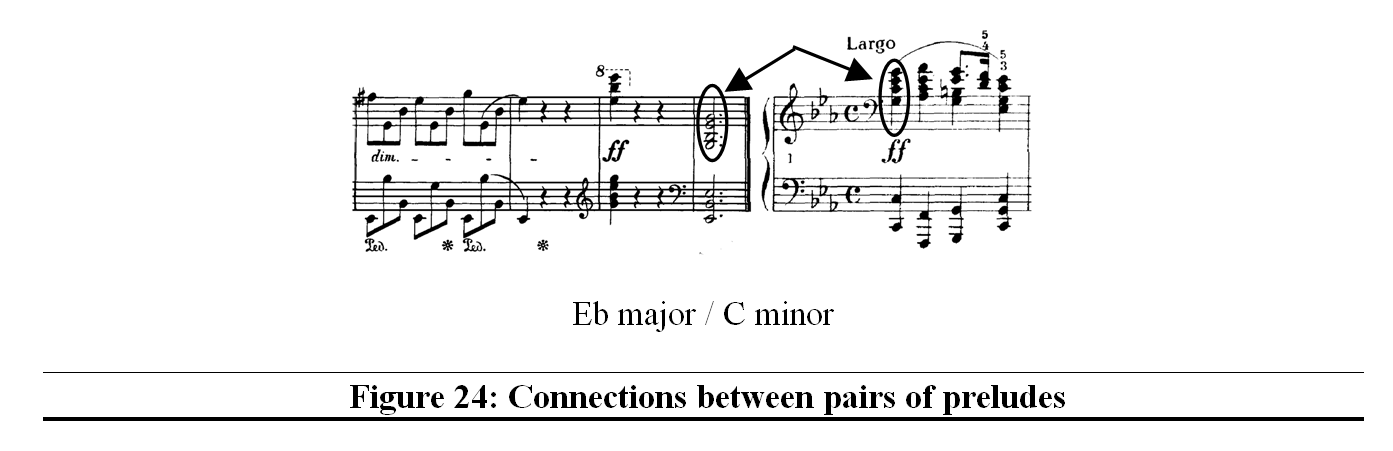

Can such an ending be found in the D minor Prelude? Remarkably, it can. The final melodic A of the F major Prelude is picked up in m. 10 of the D minor Prelude. This leads to a strong cadence in F major (mm. 10-15). Furthermore, the voicing of the F major chord in m. 15 recaptures the exact bass and soprano notes that outline the final chord of the F major Prelude (see Figure 30).

So this strange mirror of the first and second preludes can be found in the final two preludes. But are these overlapping beginnings and endings really so strange?

A recurring motive found throughout the entire set of preludes has been the anadiplotic overlap of (on the lowest level) the end of one phrase with the next and (on the next higher level) the end of one prelude with the next. These "bizarre propositions"--that the first two and the last two preludes overlap by entire phrases--become somewhat less bizarre when they are seen as the same kind of dovetailing taken just one step further.

Postlude: The Preludes as a Set

Should the Preludes be heard and played as a set?

There is no doubt that the Preludes were conceived and written as a set, and that the set as conceived has a definite beginning, middle, and end. But does this mean they should be performed as a set?

Summarizing the main reasons to consider the Preludes as a set:

Performing the Preludes as a set, hearing the set as a whole in its

variety and unity, is certainly an attractive option. But performers should

not neglect, either, to perform the preludes as Chopin did, in small sets

or grouped with other works. The Preludes, whether performed alone or together,

are part of a whole, but that hidden whole can be heard with the inner

ear even when a only few preludes are performed, and must still be heard

with the inner ear, even when all the preludes are performed.

Maurice Ravel: Valses Nobles et Sentimentales

The title Valses nobles et sentimentales sufficiently indicates my intention of composing a series of waltzes in imitation of Schubert. The virtuosity which forms the basis of Gaspard de la nuit gives way to a markedly clearer kind of writing, which crystallizes the harmony and sharpens the profile of the music.16

Maurice RavelLike Chopin's Preludes, Valses nobles et sentimentales is a major work composed of a series of smaller parts. And like the Preludes, it is a work with a strong debt to an earlier composer. Chopin's model was J. S. Bach; Ravel's model was Franz Schubert. Schubert had written dozens of Viennese-style waltzes, some of which he labeled "Valses nobles" and others "Valses sentimentales".

As Ravel suggests in his autobiographical comment, this set of waltzes does mark a new style for him. The harmonies, although based on the same principles as his earlier works, are here sharper and more pungent. The waltz, the phenomenon that held all Europe in thrall for over a hundred years, had up to this time been of but passing interest to Ravel. Few would have guessed that Ravel would be drawn to this popular and rather frivolous genre: the works immediately preceding the Valses had been serious and rather difficult.

The superscription on the waltzes, from Henri de Régnier, reads " . . . le plaisir délicieux et toujours nouveau d'une occupation inutile." (" . . . the delicious and ever-changing pleasure of a useless occupation"). The Valses, then, were meant to be a pleasant diversion, perhaps even a bit frivolous. Yet all this frivolity is to be viewed with a certain degree of ironic detachment--what Hélène Jourdan-Morhange calls the "'good-bad taste' style intended by Ravel".17

Perhaps it is this side of the work that led such a large proportion of the audience at the premiere of the Valses astray. The Société Musicale Indépendante (S.M.I.), with which Ravel had been closely allied, was presenting, as an experiment, concerts of new works in which the composer was not identified. The audience heard the works free of pre-conceived notions and at the end was asked to guess the composer. Ravel was correctly identified as the composer of the Valses by slightly more than half of the audience at its 1911 premiere, but the work was booed and hissed by audience members--presumably those who did not recognize the composer. Ravel's friend Cipa Godebski, seated next to him, asked him "what idiot could have written such a piece."18

Presumably the relatively sophisticated audience members of SMI immediately detected the "bad taste" of the Valses' deliberately overdrawn sentimentality and melancholy, stereotypical waltz rhythms, and other emotional excesses, but missed the subtle and delicious irony with which these "bad taste" elements are presented. Ravel himself is half drawn into the noble and sentimental world of the waltzes, but the listeners at S.M.I. who heard only this half of the waltzes were missing something vitally important for understanding them.

Despite its inauspicious premiere, Valses soon proved to be popular with performers and audiences. In 1912, Ravel was asked to orchestrate the waltzes to form the basis of a ballet, which was called Adélaïde, ou le langage des fleurs (Adélaïde, or the Language of Flowers). A dramatic scenario was written for each waltz; the scenarios revolve around the courtesan Adélaïde, her love affairs, and the symbolism of flowers.

The waltzes do unquestionably alternate between the more vigorous and the more reflective. The first waltz is of the more vigorous variety, and the opening chords, with their pungent dissonances, may be a good part of the reason the audience at S.M.I got off on the wrong foot with the Valses:19

|

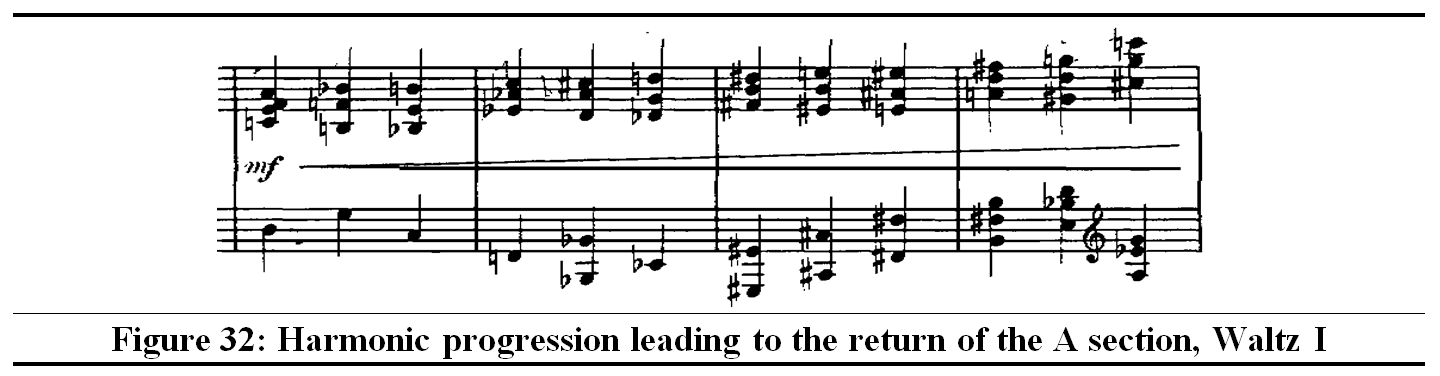

The waltz is in ABA form, with the B section continuously developing and transforming the motives presented in the A section. The rhythm and harmony of the initial four measures are transformed in two ways, first melodically (see Figure 31) and then harmonically. The harmonic development culminates in a remarkable chord progression, based on the harmony established in the initial four measures, that leads into the restatement of those four measures in the recapitulation (see Figure 32).

The initial melodic germ, based on the waltz's opening motive (m. 21)

The first expansion of the motive (m. 25)

A second expansion (m. 29)

A third expansion (m. 33)

A variant of the previous expansion (m. 39)

Waltz II: Assez lent-avec une expression intense

Clearly in the "sentimentale" category is the second waltz: its opening motive is a series of sighing augmented chords. When the sigh motive returns, it is as the final part of a longer phrase, and this together with the harmonic context gives the impression that the listener has broken into a waltz already in progress, having missed the "real" beginning of it (see Figure 33).

| Length: | 8 | 8 + | 8 | 8 | 4 + | 4 | 8 + | 8 | 8 |

| Material: | a2 | a1 | a2 | b | a2I | a1I | a1 | a2 | b |

| Measure no.: | 1 | 9 | 17 | 25 | 29 | 33 | 41 | 49 | 57 |

Figure 33: Phrase analysis of Waltz II

In m. 17 and m. 49, phrase a2 is revealed as the culmination of a1; thus the numbering of those phrases. Phrases a1I and a2I are inversions of a1 and a2, respectively.

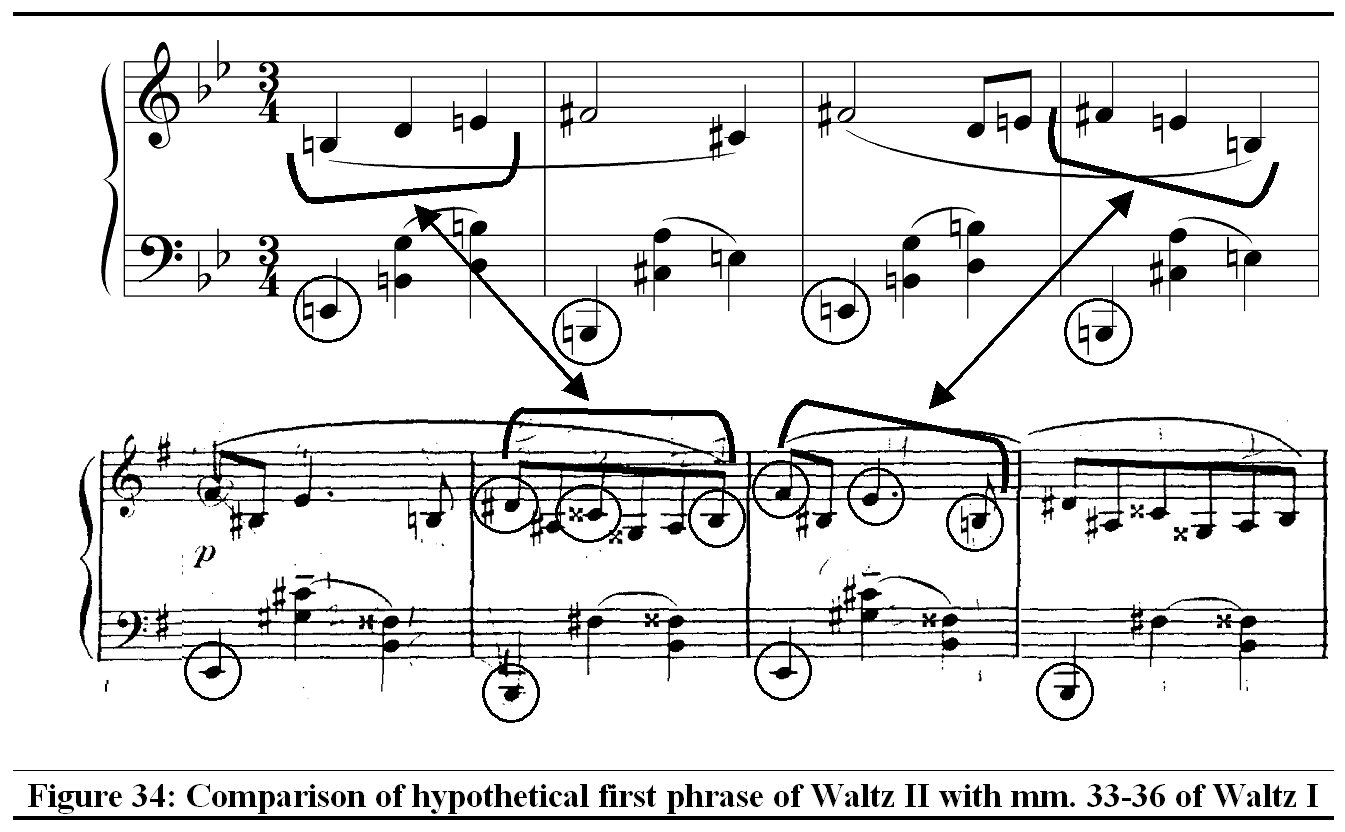

Perhaps it is too much to expect that, as in the Chopin Preludes, the second movement's "missing" initial phrase will appear secretly in the first movement. Nevertheless, if the a2 phrase is projected backwards, there is a certain resemblance between this "missing" phrase and a phrase in the first waltz's B section (see Figure 34).

Regardless of the exactness or inexactness of the parallels in these two phrases, starting the second waltz in the middle of a phrase means that something is missing in its beginning. The first waltz, in the right place at the right time, rushes to fill in the gap, and the result is that the boundary between Waltzes I and II is blurred and the connection between them strengthened.

Waltz II is the slowest waltz of the first four, and Waltzes III and IV each move the tempo up a notch. This is part of a general plan to build intensity through the climax at Waltz VII and then release it in the final waltz.

Waltz III consists of a series of waltz phrases, each phrase repeated immediately with variation. The first phrase is repeated with fuller orchestration; the second phrase, on repetition, has a lighter orchestration and a change in articulation that creates a hemiola effect. The third phrase is repeated at a higher pitch level; after a short transitional phrase, the first phrase returns. A codetta-like extension of this final phrase concludes the waltz and leads directly into Waltz IV.

In a set of 8 waltzes, the waltz rhythm can easily become monotonous. Hemiola figures are a primary source of rhythmic variety throughout the entire set. Waltz IV is built entirely on a hemiola rhythm in the right hand, while the left hand generally supports the underlying 3/4 meter, only occasionally defecting to join the right hand's hemiola. Each phrase in the waltz begins with the rhythmically "dissonant" hemiola rhythm, only resolving back to the underlying meter at phrase end.

Waltz V: Presque lent--dans un sentiment intime

Waltz V represents a break in the momentum that has been increasing through the last three waltzes, and will continue in Waltzes VI and VII. The inscription clearly places this in the "sentimental" group of waltzes.

Every phrase of the waltz is built on the initial four-note melodic motive. The fifth and sixth phrases are further removed but still show an unmistakable derivation from this melodic germ (see Figure 35).

Figure 35: Transformation of the initial melodic motive in four phrases of Waltz V

In the A section of this lively waltz in ternary form, the hemiola figure is again prominent, but now the left hand plays hemiola rhythms while the right hand supports the meter.

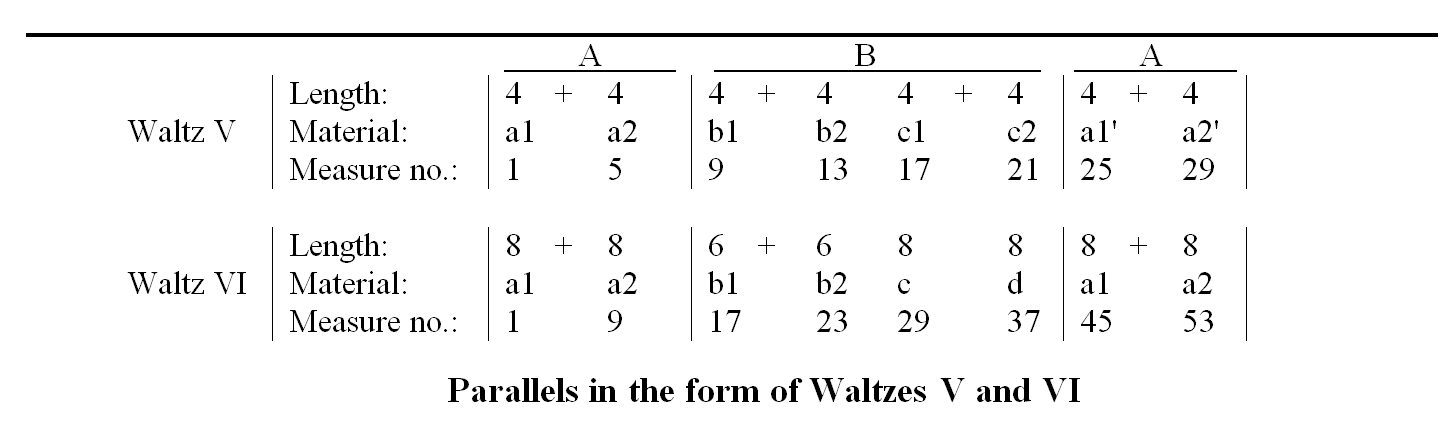

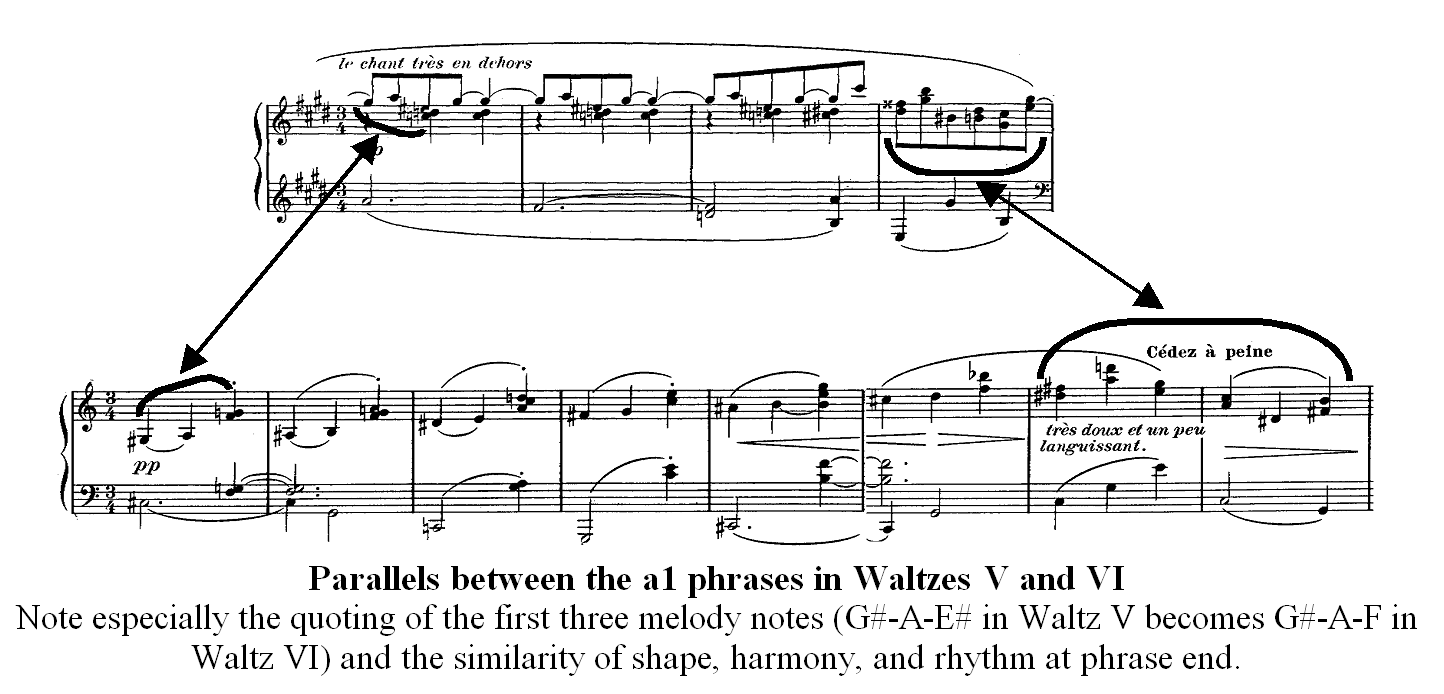

In the dance suite of the Baroque era, it was quite common for pairs of dances to appear, the first dance typically slower, and the second dance a variation or re-composition of the first. Most often there is a metrical change involved (duple meter to triple or simple to compound). Could Waltzes V and VI be such a related pair? Waltz V is slow, while Waltz VI is lively. Although Waltzes are in 3/4 time, there is a significant metrical shift between the two, because of the difference in tempo. In the slower tempo of Waltz V (Ravel indicates quarter note=96), the quarter note is felt as the main beat, and the quarter note is always divided into two eighths. The overall effect is a simple triple meter. With the faster tempo of Waltz VI (Ravel indicates dotted half note=100), the dotted half note as the main beat, and invariable four-bar phrases, the listener's impression (although not the notated meter) is of compound quadruple time.

The tempo relationship and metrical relationship is right, but what is the melodic relationship between the two waltzes?

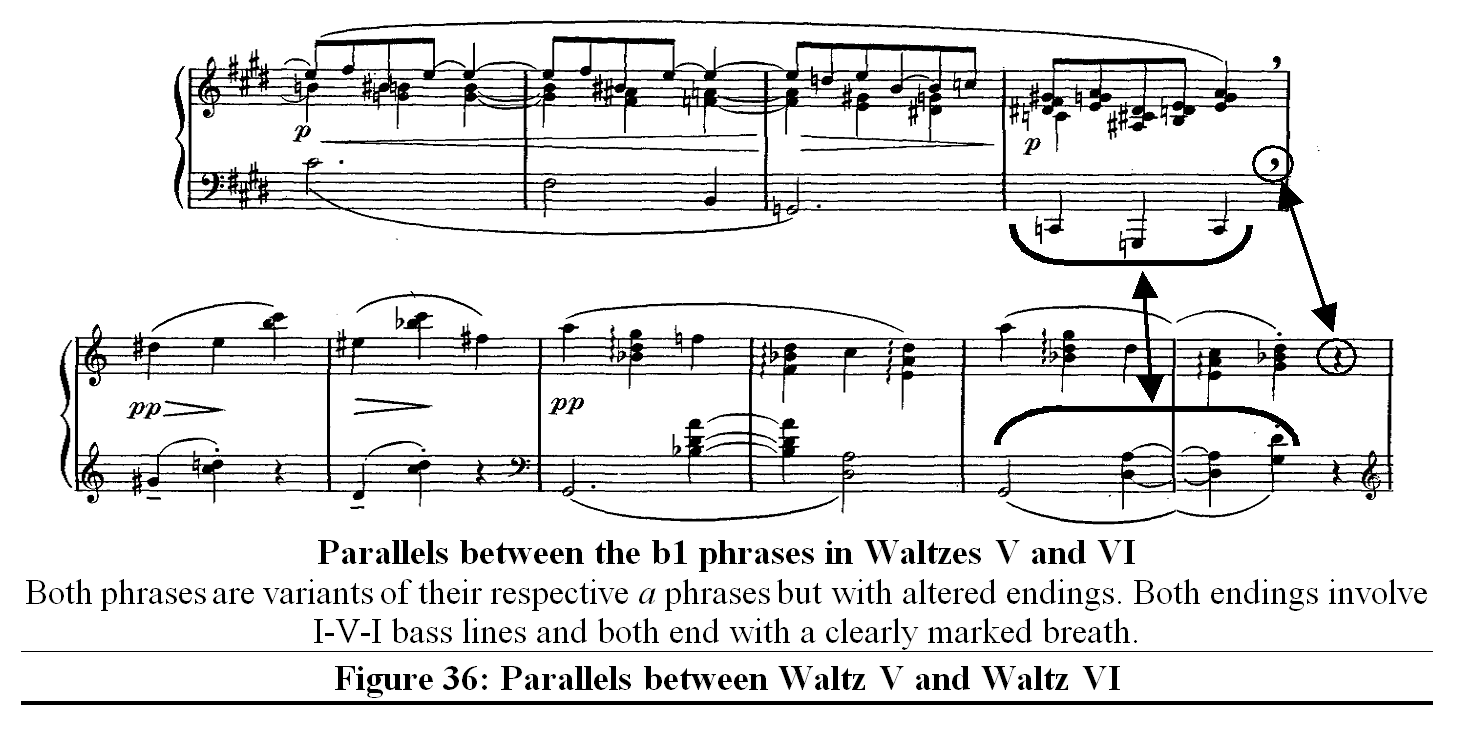

A phrase-by-phrase comparison of the two waltzes reveals that at key points a close relation exists between important melodic notes and melodic shapes. In addition, the two waltzes are clearly parallel in form (see Figure 36).

The seventh waltz seems to me the most characteristic.20

Waltz VI-final 2 measures Waltz VII-first 2 measures

The overall form of Waltz VII is ternary:

| Intro | A | B | Transition | A |

A different tempo, texture, and melodic content distinguish the B section from the A section. This is the only waltz with such a distinct middle section, and the more extended form gives weight and emphasis to this waltz, which is the climax of the set.

Ravel wrote an analysis of the main theme of the B section that is very revealing about his compositional process and use of harmony (see Figure 38). This passage could be analyzed as an example of bi-tonality or other uncontrolled use of dissonance, but it is interesting that Ravel reduces the passage to a conventional harmonic framework with conventional non-harmonic tones (passing tones and neighbor notes, for the most part). Some of the resolutions are omitted (elliptical or "understood" in context), but the point remains that Ravel himself considered his most striking harmonic innovations to be not rule breaking, but rather logical extensions of the conventional rules of harmony and use of dissonance.

With regard to unresolved appoggiaturas, here is a passage which may interest you. . . .

. . .

This fragment is based on a single chord:

which was already used by Beethoven, without preparation, at the beginning of a sonata [Beethoven's Op. 31 No. 3]:

Here now is the passage with the appoggiaturas resolved; actually, the resolution does not occur until measure A [measure 78, the end of the period] when the chord changes.

The E [(a) and (b)] does not change the chord. It is a passing tone in both cases.

Figure 38: Ravel's own analysis of the B section of Waltz VII21

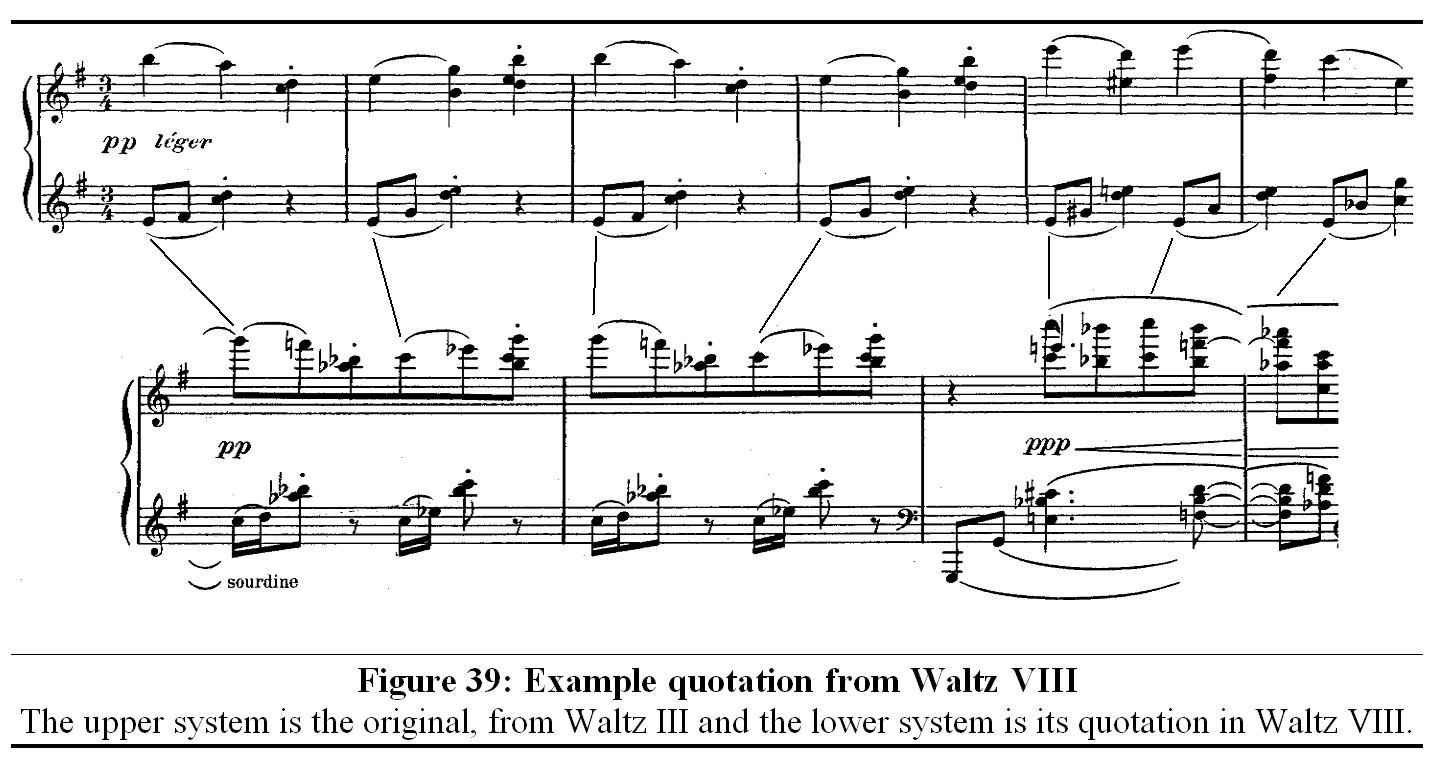

The most typically impressionistic moment in Valses nobles et sentimentales comes in the Épilogue. The movement starts at lent ("slowly"), moves to plus lent ("more slowly"), later mème Mouvt un peu plus las ("same tempo but a little more tired"), and so on. Embedded within this glacially slow movement, so motionless that it almost seems to freeze time itself, are brief fragments and reminiscences of previous waltzes (see Figure 39). In the words of Gerald Larner, it is "the supreme example of the impressionist recapitulation."22

As there was in Chopin's final prelude, in the final waltz there is a mystery. Themes and motives from all the previous waltzes are quoted, except one: Waltz V. This seems puzzling--ample space exists in the Waltz's rather loose form for any number of quotations, and in fact several waltzes are referred to multiple times.

The mystery is solved, of course, when we remember that Waltz VI is the "double" of Waltz V. The epilogue's three references to the initial phrase of Waltz VI are, at the same time, veiled references to the initial phrase of Waltz V.

The waltz ends with a quotation of the a1 theme of Waltz II--a theme

that may itself be a veiled quotation of the first waltz--and what gesture

could bring the set to a more fittingly ambiguous conclusion?

Béla Bartók: Piano Sonata (1926)

1926 has been called Bartók's "Piano Year".23 That year he completed part of the Mikrokosmos and all of Out of Doors, Nine Little Piano Pieces, the First Piano Concerto, and the Piano Sonata.

A number of Bartók's artistic concerns during this period came together to make the Piano Sonata unique--the only sonata for piano of his mature years. Bartók as a performer and teacher was an heir to the romantic, virtuosic Hungarian tradition of piano performance: his primary teacher was István Thomán, a pupil of Franz Liszt. Yet Bartók in his own performances did not confine himself to the romantic virtuoso literature, but covered a wide swath of the standard and lesser-known repertoire. In his recital repertoire, he seemed to favor Beethoven and Bach24 and in 1926 he performed a group of Italian pre-classical works by Zipoli, Rossi, Pasquini, and others.25 He also performed contemporary works as diverse as Ravel, Reger, the neo-classicism of Stravinsky, and early 12-tone works of Schoenberg. In the early 1920s, he met the avante-garde experimentalist Henry Cowell in London.26 And perhaps most important, Bartók, working with Zoltán Kodály, had amassed a huge catalog of notes, transcriptions, and recordings of the folk musics of central and eastern Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Bartók was particularly interested in the comparative study of folk music in different cultures; his own music is influenced not as much by the music of one particular country or region as by a distillation of the most effective ideas and procedures from all the musics he studied. Bartók thought very highly of folk music and music-making procedures, considering them in every way the equal of art music.27

All these disparate threads of Bartók's life and thought converge to create the Piano Sonata: it is classical in form, virtuosic in difficulty, modern in color and harmony, pre-classical in its spare texture, and infused in every note with the spirit and feeling of folk music.

The sonata's first movement begins with a forceful statement of the Introductory Material (I) that leads directly into an equally forceful statement of the a material (m. 14). The Introductory Material (I) begins with a three-note motto (the i motive, see Figure 41a) leading into a motoric rhythmic figure. The i motive and the motoric figure are repeated, developing and expanding the ideas, and then repeated again. Only on this second repetition have these rudimentary materials been developed sufficiently to be considered a real phrase with beginning, middle, and end; this is the beginning of the a material (mm. 13-18, see Figure 46). The a material appears, then, not as a sudden departure from the previous material, but as an organic development of it. This organic development process continues: the end of the a phrase is extended and developed in mm. 23-35, the material finally dissolving to a two-note motive that has developed step-by-step from, and is clearly related to, the i motive (see Figure 41b). At the end of the B1 section, through a similar process of organic melodic development, a similar two-note stepwise figure is developed. This motive often appears at the end of phrases or in between sections and is called the t motive (t standing for "transitional") (see Figure 41c).

|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Section: | A1 | B1 | C1 | D1 | T | B2 | A2 | C2 | D2 | Coda |

| Material: | I + a + I | b + T | c | d | T,I,d | B + I | a | c + I | d | I + T |

| Measure no.: | 1 | 44 | 76 | 116 | 135 | 155 | 187 | 211 | 236 | 247 |

I and T refer to the Introductory and Transitional Material (first appearing in m. 1-13 and mm. 70-72, respectively). This material is most often used to open or close major sections of the movement. Lower case letters a, b, c, and d refer to the main melodic material of the respective sections, which is often framed by I and/or T material.

|

|

|

|

|

(m. 1) |

(mm. 33-34) |

(m. 69-71) |

|

|

|

||

|

(m. 87-88) |

(m. 116) |

||

Figure 41: Important appearances of the i motive and t motive28

In the C1 section, at the end of each of the phrases, the t motive is developed and extended further. It becomes clear that the i motive and the t motive are closely related (see Figure 41d).

Section D1 does not use the i or t motives in introductory or punctuating roles as do the previous sections, but its relation with the i motive is even more intimate: its main theme is based on the i motive in one voice in counterpoint with an inversion of the i motive in another voice (see Figure 41e).

Much of the purpose of the development section seems to be to clearly show the organic relationships among the various themes and how they all derive ultimately from the i and t motives. For instance, the t motive that begins and characterizes the T section seems to come as a natural variation at the end of a d phrase (m. 135). Development of the t motive leads to a flourish at the end of T that is repeated at half speed a measure later and turns out to be the main theme of the B section (see Figure 42).

|

|

|

|

(m. 135) |

(m. 154) |

(m. 155) |

Throughout section B2 the main b theme develops organically, step by step. The final result is a version of the i motive, and if the connection is not clear enough already, this version of i motive is followed immediately by a literal statement of the i motive in counterpoint with the B2 version of I (see Figure 43). Now the b theme has been clearly tied with the t material (at the beginning of B2) and i material (at the end of B2). In retrospect, it becomes obvious that the b theme is nothing more than a version of the t motive tied to a version of the i motive (see Figure 44).

|

|

|

(m. 172-173) |

(m. 176-177) |

Figure 43: The end of the b motive transformed into the i motive

Figure 44:

The b motive (m. 44-46) is made up of

t motive (inverted and extended) + i motive

The figure that leads into the recapitulation is a version of the i

motive

arranged as points of imitation. The first three entrances are versions

of the i motive in its original rhythm; the final point of imitation

is the same motive with a faster rhythm: the opening motive of the a

material. It is hard to imagine a more vivid aural demonstration of the

organic connection between the i motive and the a material

(see Figure 45).

Figure 45: The i motive transforms into the a motive (mm. 186-187)

A first glance at the formal outline of this first movement seems to show a form with a shower of unrelated themes (see Figure 40). I have divided the material into four main theme groups; some commentators divide the material into as many as five themes. But the discussion has made clear that these themes are not by any means a sequence of unrelated ideas. Rather, the many themes are all organically related expressions of two basic motives (the i and the t motives), and both of these motives derive from the musical idea so boldly announced in the movement's first measure. This bold announcement is no accident or aberration: Bartók is at pains to make the interrelationships among the various themes and motives as transparent and audible to the ear as possible. This type of organic development of small melodic cells is typical of much of the folk music Bartók studied, and it is here that the strongest link lies between Bartók's folk studies and his own personal musical style.

Bartók's use of the i and t motives makes a fascinating connection between the small and the large elements of this organically connected structure. The motives are used as beginnings and endings and they are used in this way consistently, on every level of the work from small to large.

At the smallest level, the motives are used to articulate the beginnings and ends of single phrases (see Figure 46). The opening phrase of the a material can be taken as an archetypical example of this function. The phrase can be analyzed this way:

i motive à expansion/development ài motive (in retrograde motion)

The entire A1 section follows this same basic scheme:

I material (mm. 1-12) à expansion/development (mm.13-37) à I material (mm. 38-43)

The phrases in section C1 end with a brief flourish based on the i/t motive, while the same type of ending in section D1 is greatly expanded and, in fact, proves to be the first section of the development--an entire section (T) based on variants of the i and t motives. In the same way that the t motive articulates the end of phrases in the C1 section, the T section articulates the end of the exposition.

At the largest level, the entire movement is framed by material based on the i motive: the I theme that introduces the work is also the basis of the coda (m. 247-268). Thus we have a familiar diagram outlining the entire movement:

|

(mm. 1-53) |

à |

(mm.54-246) |

à |

(mm. 247-268) |

It is exactly this similarity in the way Bartók handles the small and the large elements of his form that makes the word "organic" especially suitable to describe them. As the smallest sapling and the mightiest oak both follow the same natural laws of growth and development, so, too, do the smallest phrase and the largest section within Bartók's Sonata.

Movement II-Sostenuto e pesante

The main conflict of the second movement is introduced in its first three measures: the left hand sounds a dissonant chord four times and the right hand answers with a single E repeated nine times (see Figure 47). The opposition single note/chord is present, in different guises, in every theme of movement.

The movement, which is slow and dirge-like, builds inexorably to a tremendous climax in mm. 42-48; the remaining fourteen measures dissipate the energy that has built up. The movement's three main musical ideas (see Figure 48) are developed organically throughout the movement, in a process similar to that used in the first movement.

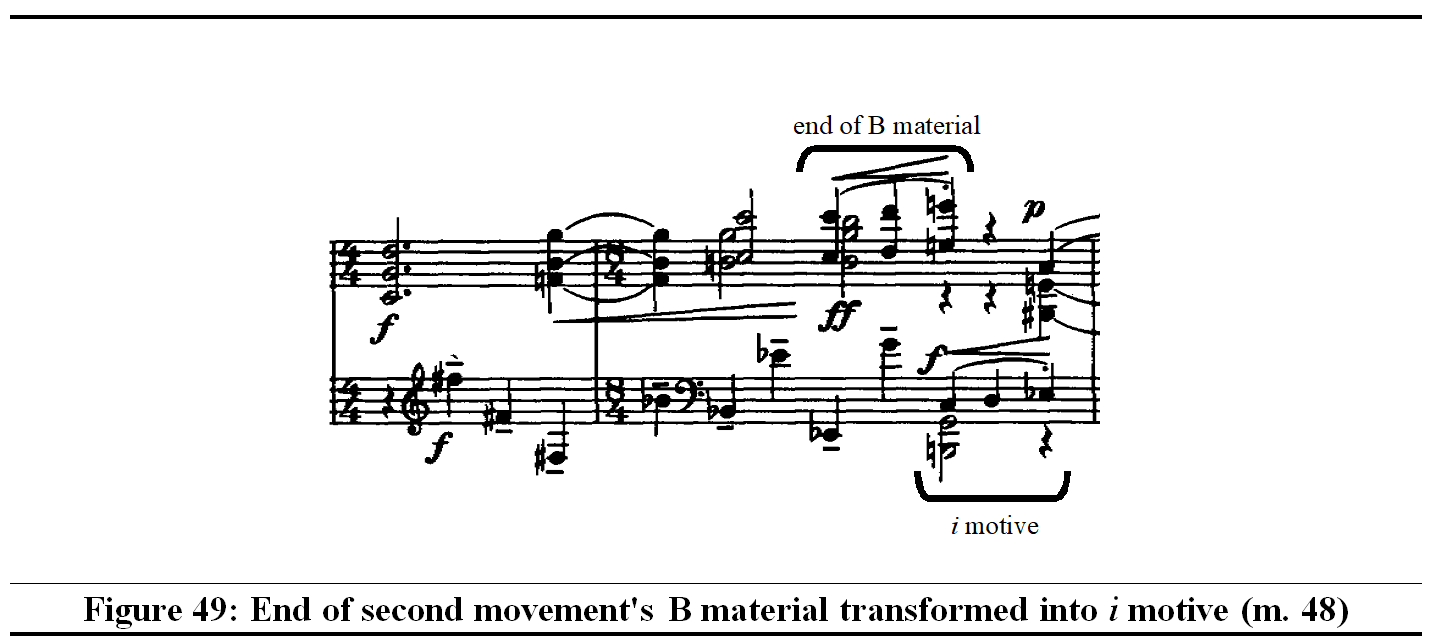

In its final stage of development (mm. 52-58) the three-note stepwise rising figure that ends the B material takes on an added significance: up to this point the steps in the figure have always been whole step-whole step. Starting in m. 52, the steps change to whole step-half step. This makes the motive identical to the i motive that generated the sonata's first movement (see Figure 49). The end of the B3 section (mm. 52-58) is built entirely on this motive.

| Section | A1 | B1 | C1 | A2 | B2 | C2 | A3 | B3 | A4 |

| Measure no. | 1 | 7 | 13 | 15 | 24 | 30 | 42 | 47 | 59 |

The first phrase of the sonata's second movement consists of the single note E. In the second phrase, a final D is added to the string of Es. In the A2 section, A and G are added so that the concluding gesture becomes E A G D G A. This is further developed in A2 and A4; the final and most developed version of the sequence in the movement is the palindromic E D A G A D E (m. 60-61). This is a typical example of Bartók's method of organically developing small melodic cells.

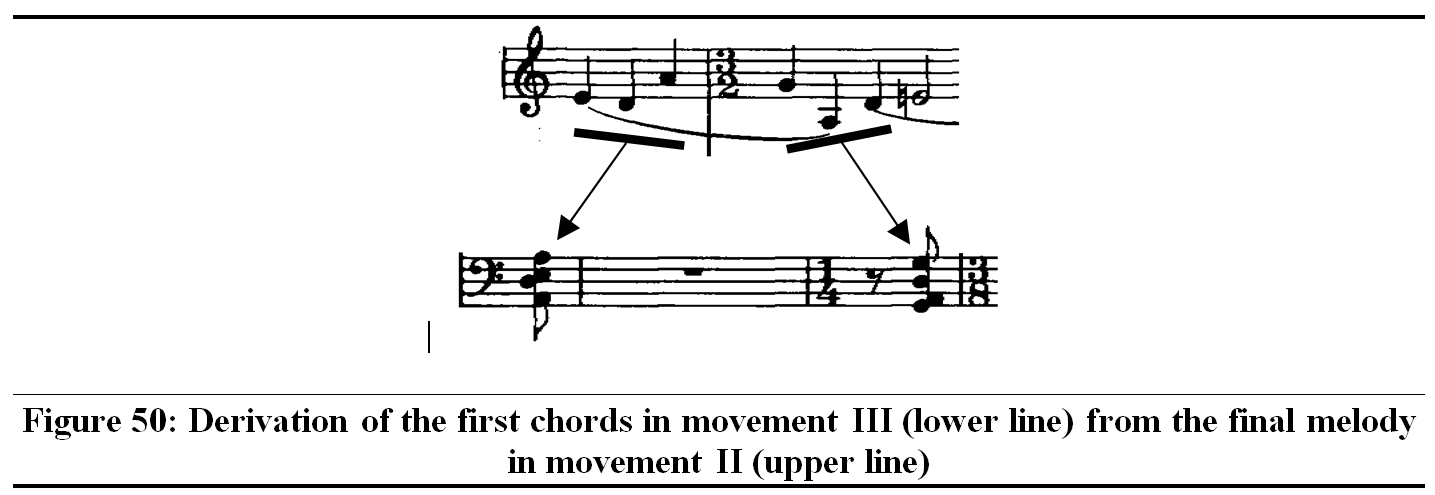

What follows is also typical Bartók: the first chord in the third movement (m. 2) represents the first three notes of the palindromic melody (E D A) while the second chord represents the next three notes (G A D). As the movement progresses, the entire harmonic basis of the movement grows from these two initial chords that are built from from the final melodic gesture of the second movement (see Figure 50).

The basis of the third movement's opening motive derives from the same source: considering pitch classes only and arranging the notes in order from highest to lowest, the palindromic melody becomes A G E D. The pitches of the opening motive are F# E C# B, simply a transposition of A G E D.

In the response to this initial motive (m. 3-4), the final three notes (C# D# E) do not fit into this scheme. Instead, they are a version of the i motive, exercising its conclusatory role as it did in the first movement.

Although the first theme is developed and expanded throughout the movement, the three notes forming the i motive remain unchanged. They retain their identity and are not developed. In the second half of the main theme (mm. 5-8), the i motive is initially absent, but as the theme is developed throughout the movement, a version of the i theme is eventually added (m. 106). The thrust of the theme's development throughout the movement, then, highlights and increases the importance of the i motive within the theme.

The cluster chords that appear in several places throughout the movement seem a typical Bartókian invention: they are a logical extension of the chords built on seconds that begin the movement. For instance, the cluster chords in mm. 85-91 grow by extension in much the same way Bartók's melodies do (see Figure 51). Surprisingly, though, the cluster chords are not Bartók's original idea: when Bartók met Henry Cowell in London, he heard Cowell perform his works based on cluster chords and discussed the idea of cluster chords with him.29 Bartók even found it necessary to write Cowell and ask permission to use the cluster chord technique in his sonata. Whatever the origin of the idea, Bartók's use of cluster chords is quite different from Cowell's, reflecting Bartók's own views of both compositional and performing technique.

Figure 51: Organic growth of cluster chords in movement III (mm. 83-91)

The third movement is generally a rondo form; the theme is continuously developed and the episodes are based on the theme or developed versions of it. The theme itself, with its quick tempo, irregular rhythm, frequently changing meter, and the emphasized reiteration of its final note, is based on the rhythm and feel of the Rumanian colinda, a kind of Christmas carol. The theme's parallel octaves may be intended to imitate the magadizing sound of folk singers.30

The rhythmic thrust of this movement is a central unifying feature, as it was with the first movement, and it is significant that Bartók removed an extended episode, initially planned, that would have seriously interrupted the rhythmic direction (the excised episode became the movement "Musettes" in Out of Doors). Like the first movement, the third movement comes to a driving rhythmic conclusion, the drive coming from a brilliant series of rhythmic chords that sum up the important harmonic vocabulary of the movement.

1. F. E. Kirby, A Short History of Keyboard Music, (New York: The Free Press; reprint, Kansas City: Roo Pak Custom Publishing & Copyright Service, 1994), 97.